Marrying the old and the new

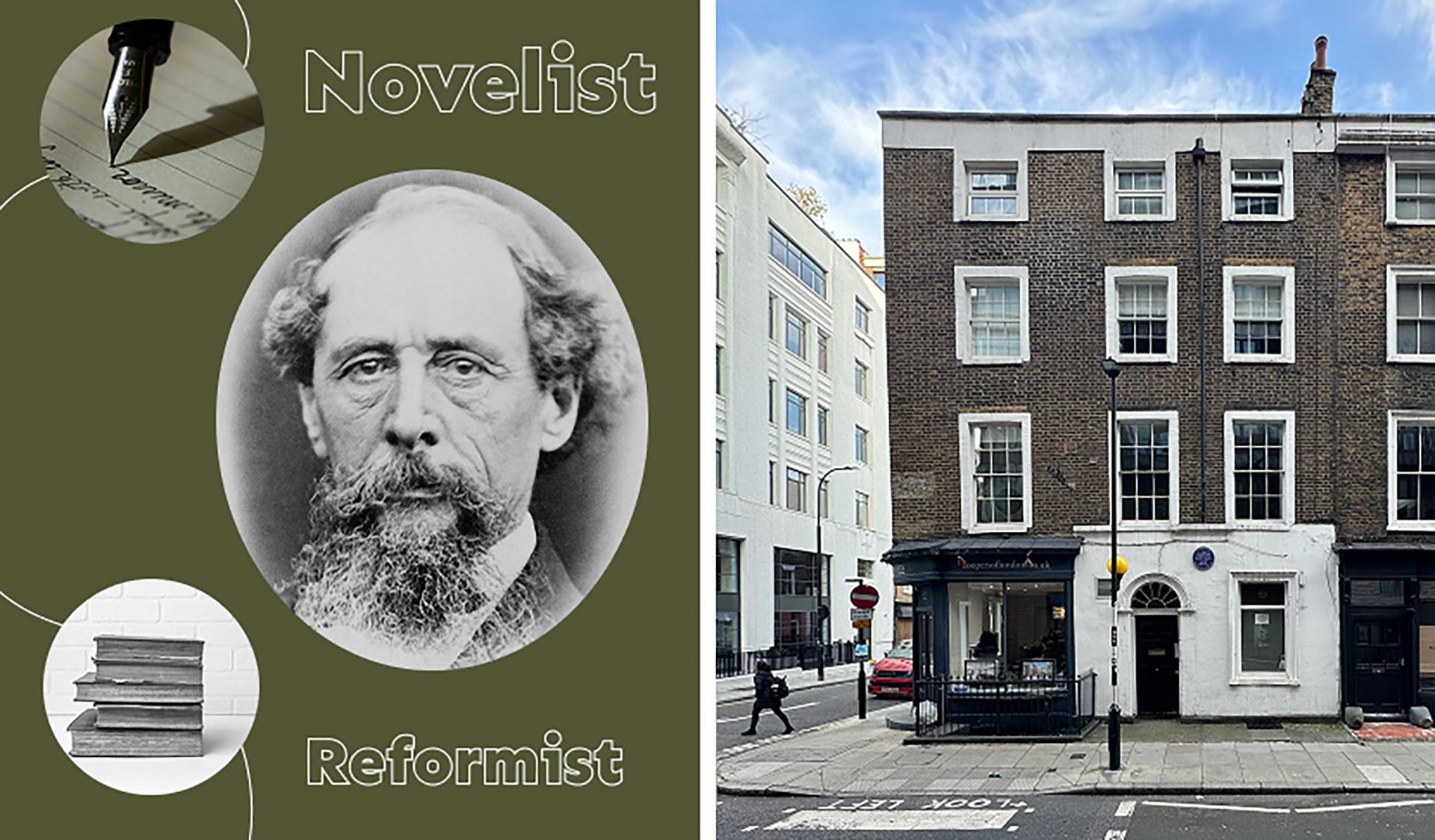

What are the challenges of developing a central London site that includes a Georgian workhouse that might have inspired a classic novel? This was the scenario facing Llewelyn Davies in London’s Fitzrovia. Zahra Lodhi, Associate and Design Team Leader on the Retained Buildings aspect of the Bedford Passage scheme, explains:

Our site between Cleveland and Charlotte Streets was owned by the University College London Hospitals Charity (UCLHC) whose original idea was to clear the existing buildings for new housing. By 2015, however, when Llewelyn Davies got involved, the brief had changed radically.